Tennessee contests disabling an inmate’s heart device at a hospital on execution day

NASHVILLE, Tenn. (AP) — A judge’s order to take a Tennessee death row inmate to the hospital on the morning of his execution so doctors can deactivate his heart-regulating implant would cause “chaos,” state attorneys said in an appeal.

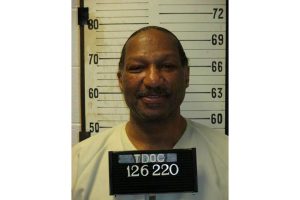

The argument was one of several in a filing Wednesday that seeks to overturn an order to deactivate Byron Black’s implanted cardioverter-defibrillator, including when and where to do it. Black is scheduled to die by lethal injection on Aug. 5 at 10 a.m.

His attorneys say his heart device would continuously shock him in an attempt to restore his heart’s normal rhythm during the execution, but the state disputes that and argues that even if shocks were triggered, that Black wouldn’t feel them.

Officials said they would need to transfer Black through Nashville the morning of his execution to comply with a judge’s order, and that the trip would create security risks, including from protestors. It’s about 7 miles from Riverbend Maximum Security Institution to Nashville General Hospital.

Kelley Henry, Black’s attorney, said the state presented “zero evidence of security risk” and said state officials were the ones who made the proposed time and place of the hospital procedure public.

The Tennessee Supreme Court is taking up the appeal and fast-tracking it.

A judge sided with Black’s attorneys last week, initially ruling that the state must turn off the heart device in the minutes just before the execution.

Black is set to die by a single dose of the barbiturate pentobarbital.

His cardioverter-defibrillator is a small, battery-powered electronic instrument that is surgically implanted in someone’s chest, usually near the left collarbone. It can be deactivated with a handheld machine, but the state says Black’s doctors have refused to come to the prison to do it.

The state asked the judge to either overturn the order about the deactivation or allow the Tennessee Department of Correction to take Black to the hospital for it the day before his execution. After a hearing Tuesday, the judge adjusted his order to say the state needs to take Black to the hospital the morning of his execution rather than deactivating the device minutes before it.

Henry told the judge the deactivation needs to happen immediately before the execution so authorities don’t risk accidentally killing Black just before a possible reprieve.

In its appeal, state has repeated arguments that the lower-court judge lacked authority to order the device disabled.

The state is now saying that the order to transport Black to the hospital the morning of the execution presents a “very real risk of danger to TDOC personnel, hospital patients/staff, the public, and even Black.”

Henry said there’s “no appreciable difference” between transporting Black Aug. 5 or Aug. 4, which is when the state proposed taking him to the hospital after the judge ordered the deactivation. She also said there’s no risk in the transportation.

“Mr. Black cannot walk,” Henry said. “He is a frail, 69 year old man, with a history of clear conduct. And the idea that the group of pacifists who protest executions by prayer would in some way create a ruckus during transport is simply not believable.”

Black was convicted in the 1988 shooting deaths of girlfriend Angela Clay, 29, and her two daughters, Latoya, 9, and Lakeisha, 6. Prosecutors said he was in a jealous rage when he shot the three at their home. At the time, Black was on work-release while serving time for shooting and wounding Clay’s estranged husband.

Black’s motion related to his heart device came within a general challenge he and other death row inmates filed against the state’s new execution protocol. The trial isn’t until 2026.

___

Travis Loller in Nashville contributed to this report.

By JONATHAN MATTISE

Associated Press