BELEM, Brazil (AP) — United Nations climate talks in Brazil reached a subdued agreement Saturday that pledged more funding for countries to adapt to the wrath of extreme weather. But the catch-all agreement doesn’t include explicit details to phase out fossil fuels or strengthen countries’ inadequate emissions cutting plans, which dozens of nations demanded.

The Brazilian hosts of the conference said they’d eventually come up with a road map to get away from fossil fuels working with hard-line Colombia, but it won’t have the same force as something approved at the conference called COP30. Colombia responded angrily to the deal after it was approved, citing the absence of wording on fossil fuels.

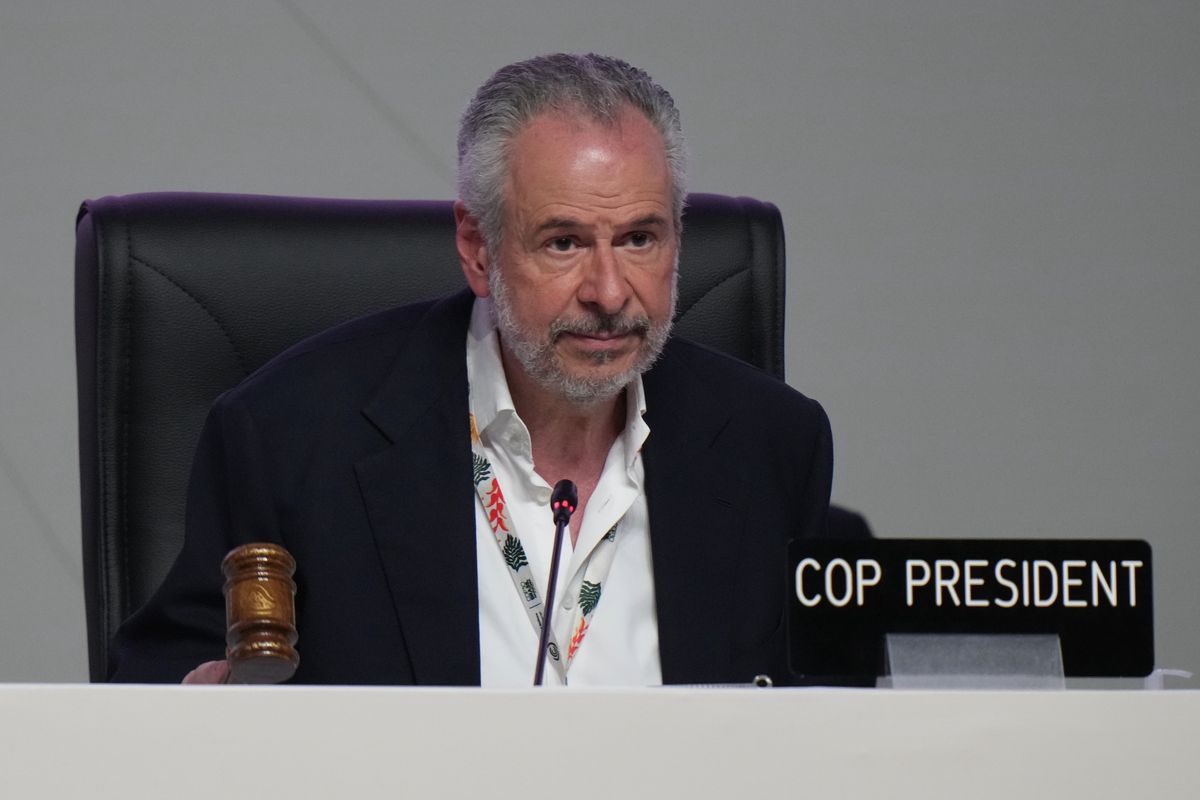

The deal, which was approved after negotiators blew past a Friday deadline, was crafted after hours of late night and early morning meetings in COP30 President André Corrêa do Lago’s office.

Do Lago said the tough discussions started in Belem will continue under Brazil’s leadership until the next annual conference “even if they are not reflected in this text we just approved.”

U.N. Secretary-General Antonio Guterres said the deal shows “that nations can still come together to confront the defining challenges no country can solve alone.” But he added: “I cannot pretend that COP30 has delivered everything that is needed. The gap between where we are and what science demands remains dangerously wide.”

Deal gets mix of lukewarm praise and complaints

Many gave the deal lukewarm praise as the best that could be achieved in trying times, while others complained about the package or the process that led to its approval.

“Given the circumstances of geopolitics today, we’re actually quite pleased with the bounds of the package that came out,” said Palau Ambassador Ilana Seid, who chaired the coalition of small island nations. “The alternative is that we don’t get a decision and that would have been a worse alternative.”

“This deal isn’t perfect and is far from what science requires,” said former Ireland President Mary Robinson, a fierce climate advocate for the ex-leaders group The Elders. “But at a time when multilateralism is being tested, it is significant that countries continue to move forward together.”

“This year there has been a lot of attention on one country stepping back,” U.N. climate chief Simon Stiell said, referring to the United States’ withdrawal from the landmark 2015 Paris agreement. “But amid the gale-force political headwinds, 194 countries stood firm in solidarity — rock-solid in support of climate cooperation.”

Some countries said they got enough out of the deal.

“COP30 has not delivered everything Africa asked for, but it has moved the needle,” said Jiwoh Abdulai, Sierra Leone’s environment minister. What really matters, he said, is “how quickly these words turn into real projects that protect lives and livelihoods.”

U.K. Energy Minister Ed Miliband said the agreement was “an important step forward,” but that he would have preferred it to be “more ambitious.” He added: “These are difficult, strenuous, tiring, frustrating negotiations.”

Swift final push prompts complaints

The deal was approved minutes into a plenary meeting open Saturday to all nations that were present.

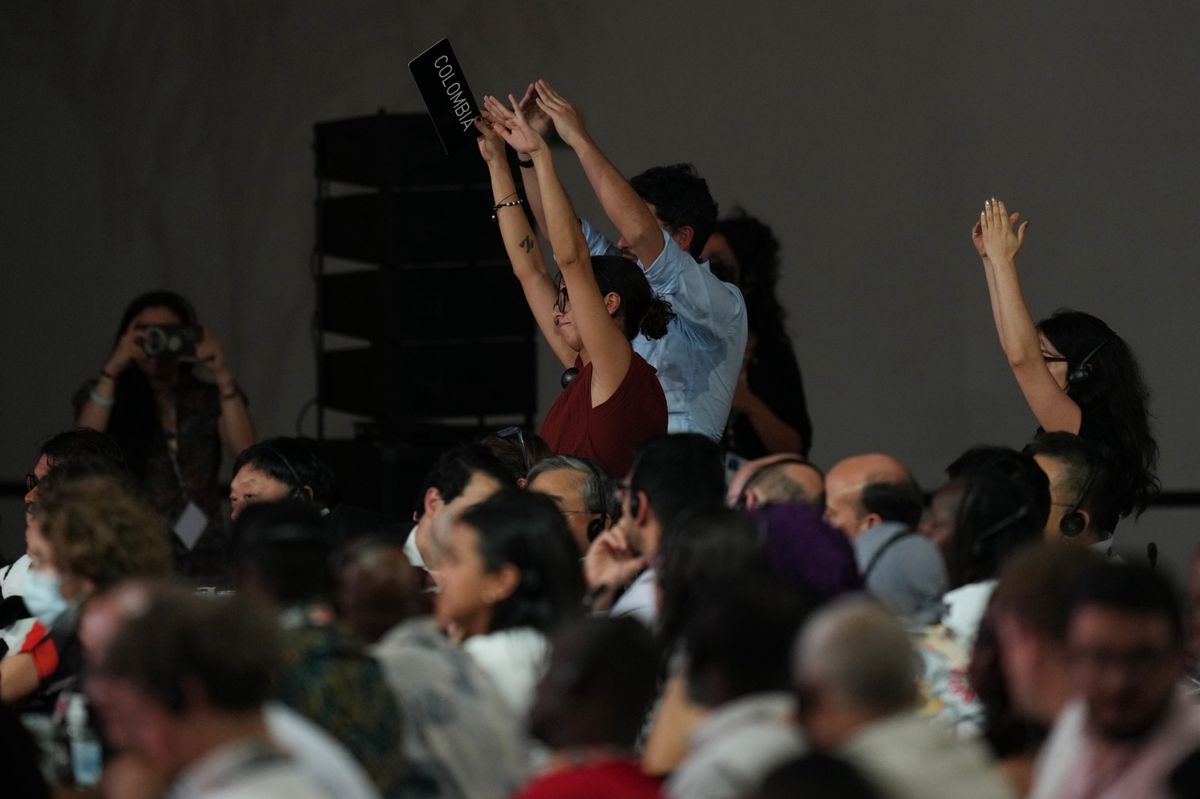

After the main package was approved — to applause by many delegates — angry nations took the floor to complain about other parts of the package and about being ignored as do Lago moved quickly toward approval. The objections were so strong that do Lago temporarily halted the session to try to calm things down.

Colombia’s Daniela Duran Gonzalez objected to sections on helping nations cut emissions and reaching worldwide temperature limits that were previously agreed upon. She blasted the conference’s president for ignoring her, saying: “The COP of the truth cannot support an outcome that ignores science.”

An area that usually gets less attention became a big point of contention. The approved deal established 59 indicators for the world to judge how nations are adapting to climate change. Before the Belem conference, experts crafted 100 precisely worded indicators, but negotiators changed the wording and cut the total.

The European Union, several Latin American countries and Canada said they had severe problems with it, calling it unclear and unworkable. They complained that they tried to object but were ignored.

Do Lago apologized.

How major issues were handled

A handful of major issues dominated the talk. Those included coming up with a road map to wean the world from fossil fuels, telling countries that their national plans to curb emissions were inadequate, tripling financial aid for developing nations to adapt to extreme weather and reducing climate restrictions on trade.

“COP30 gave us some baby steps in the right direction, but considering the scale of the climate crisis, it has failed to rise to the occasion,” said Mohamed Adow, director of Power Shift Africa.

Critics complained there was not much to the deal.

“Strip away the outcome text and you see it plainly: The emperor has no clothes,” said former Philippine negotiator Jasper Inventor, now at Greenpeace International.

Panama negotiator Juan Carlos Monterrey Gomez railed against the deal.

“A climate decision that cannot even say ‘fossil fuels’ is not neutrality, it is complicity. And what is happening here transcends incompetence,” Monterrey Gomez said. “Science has been deleted from COP30 because it offends the polluters.”

Many nations and advocates wanted something stronger because the world will not come close to limiting warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) since the mid 1800s, which was the goal the 2015 Paris agreement set.

The financial aid for adapting to climate change was tripled to a goal of $120 billion a year, but the goal was pushed back five years. It was one of several tough issues to dominate the late stage of talks. Vulnerable nations have pressed the wealthier countries most responsible for climate change to help out with money to rebuild from damaging extreme weather and to adapt to more of it in the future.

Pushing back the goal leaves “vulnerable countries without support to match the escalating needs,” Adow said.

After the main deal was approved, tempers flared as the open meeting stretched on. Russia’s ambassador at large, Sergei Kononuchenko, lectured Latin American delegates who were objecting frequently that they were “behaving like children who want to get your hands on all the sweets, and aren’t prepared to share them with everyone.”

An angry Eliana Ester Saissac of Argentina said Latin Americans “are in no way behaving like spoiled children who want to stuff our mouths full of sweets” to a roar of cheers and applause.

___

The Associated Press’ climate and environmental coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

___

This story was produced as part of the 2025 Climate Change Media Partnership, a journalism fellowship organized by Internews’ Earth Journalism Network and the Stanley Center for Peace and Security.

By SETH BORENSTEIN, MELINA WALLING and ANTON L. DELGADO

Associated Press